By Sherry Bunting, special for Farmshine, April 26, 2024 edition

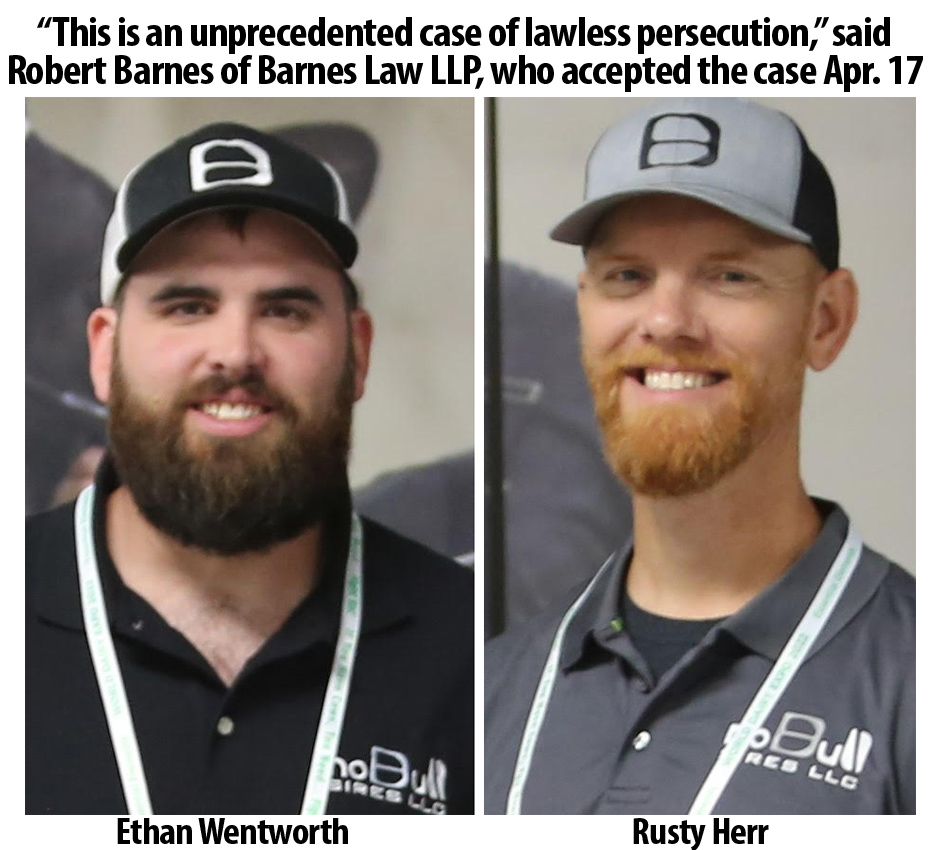

HARRISBURG, Pa. — It has been two weeks since Rusty Herr, 43, of Christiana and Ethan Wentworth, 33, of Airville were arrested on April 10 and 11 and separately incarcerated in Lancaster and York County Prisons — their respective counties of residence.

As of April 24, both men are still in jail, without bail, and without seeing a judge.

“This is an unprecedented case of lawless persecution against two farmers who help other farmers with standard breeding practices, as is their right,” said Robert Barnes, Esq. of Barnes Law LLP, who accepted the case on April 17.

“The Pennsylvania Veterinary trade organizations conspired to protect their own monopoly in violation of the law and in a manner that has hurt farmers throughout Pennsylvania. The Pennsylvania Department of State (DOS), in a secret star chamber proceeding, ordered the unlawful imprisonment of Rusty Herr and Ethan Wentworth, who have still never seen an arrest warrant, heard the charges against them, had a hearing, or seen a judge,” Barnes continued in a statement provided to Farmshine Wed., April 24.

“In short, their due process rights have been obliterated. I will seek justice for Wentworth, Herr, and their families to the fullest extent of the law,” Barnes asserted.

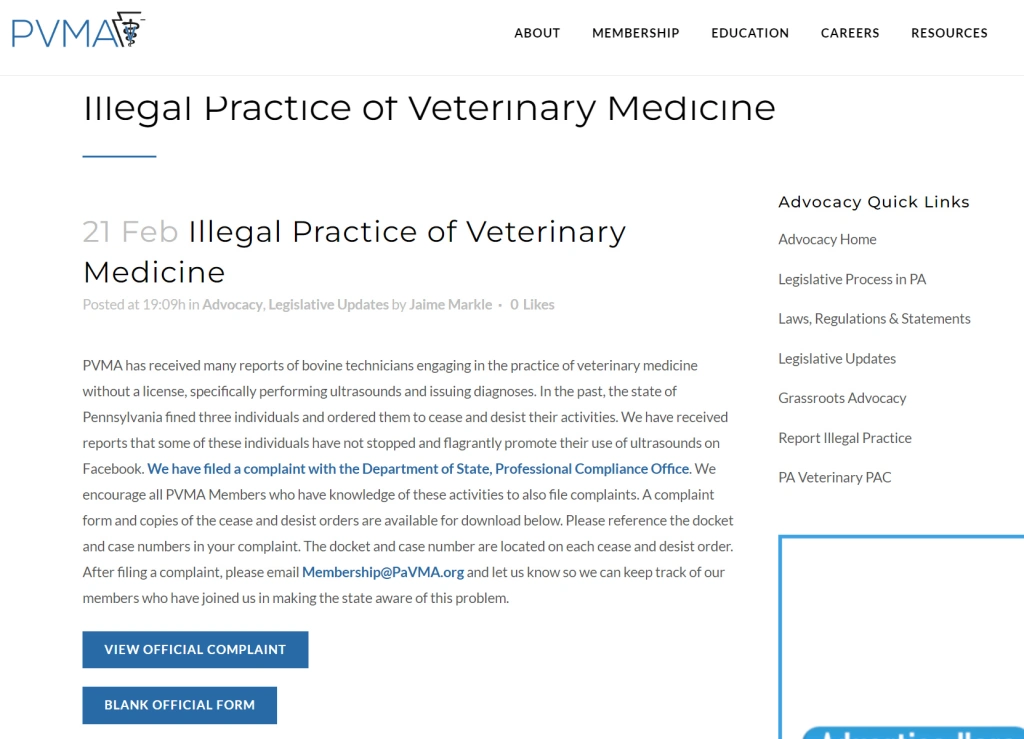

The only dockets available for prior orders last week were two found on the website of the Pennsylvania Veterinary Medical Association (PVMA) as part of a package on their “advocacy” page asking members to file complaints with DOS by referencing the provided docket numbers, and then report back to PVMA so they can keep track. One was a 2010 docket with Herr as respondent and the other 2018 naming Wentworth. Both orders stated civil penalty, not criminal.

All other court and DOS system searches yielded nothing, and even those docket numbers came up “nonexistent.”

In a PVMA press release dated April 19, the veterinary trade organization stated: “PVMA is unaware of the circumstances surrounding the arrest of two individuals on April 10 and 11 for contempt of court.”

And yet, in their 2020 Complaint that they had posted at their website before it was removed this week, the PVMA specifically stated: “Since these individuals continue to practice veterinary medicine without a license after their initial order to cease and desist, we request that the state file contempt charges with the Commonwealth Court. PVMA is able to supply additional witnesses upon request.”

Farmers, veterinarians and others in the dairy industry are discussing the case. Calls, texts and emails pour in from dairy farmers who appreciate NoBull Solutions and rely on them for breeding service.

Calls, texts and emails have also come in to make further accusations against the imprisoned men — none of which are mentioned in the PVMA complaint or their links to two previous civil orders, nor in any documentation provided now by the DOS.

After initiating a request for an interview on April 15 and submitting questions to the State Board of Veterinary Medicine on April 16, Farmshine received a few answers on April 24 from the Department of State (DOS).

On the current situation, the DOS responds: “We can neither confirm nor deny the existence of an investigation or matter.”

On the question of what hearing process may or may not have been available to Herr and Wentworth regarding past civil penalties and cease and desist orders, dockets were provided, one with Herr as the respondent in 2010, and one with Wentworth and another individual who has not been arrested named together as respondents in 2018.

“Speaking generally, the Department reviews every potential license violation of which it becomes aware, whether that is through a complaint filed directly to the Department, a notification from local law enforcement or through media reports. After review, a determination is made as to whether formal action is warranted,” the DOS press office explained in their email response.

The long and short of the DOS response here is that all respondents have due process at some point, which includes notice and an opportunity to participate in those original proceedings, call witnesses, introduce evidence, and testify on their own behalf.

Herr and Wentworth did so, on their own behalf, without legal counsel, in 2010 and 2018, respectively, according to the documents provided by the DOS.

However, they were not noticed since then by the DOS, and nowhere in the responses from DOS or the adjudications they provided is an automatic 30-day prison term without bail stated as a consequence for “continuing to violate the Act” by ultrasounding cows they do not own. No proof of the process has been shown in the responses from the DOS apart from the 2010 and 2018 actions.

On the question about where pregnancy and diagnosis are linked in the law or regulations, the bottomline is they are not. The State Board of Veterinary Medicine decides this through adjudication and orders as the legislature grants the Board this authority.

“The Board adopted the position that, ‘both the performance of a surgical procedure, such as the Gymer/Stemer Toggle Suture Repair, and the diagnosis of a physical condition, such as detecting through ultrasound whether an animal is pregnant, constitute practice of veterinary medicine,’” the DOS reported, adding that the Act contains an exception for any person or an employee of that person or agent while practicing veterinary medicine on his or her own animals. (What constitutes an ‘agent’?)

The DOS included a copy of an Amended Adjudication and Order, Docket No. 2296-57-09, which came before the State Vet Board with Herr as respondent in May of 2010. Performance of toggle on six animals he didn’t own and performing ultrasound for detection of pregnancy on animals he didn’t own were both listed specifically in the determination of civil penalty.

This was 14 years ago, and the docket from 2010 confirms that Herr responded to say he is “no longer toggling other people’s cows.”

The amended adjudication goes on to explain “should the respondent continue to violate the Act, he may be subject to the imposition of a $10,000 civil penalty per act or practice.”

Nowhere does it mention automatic 30 days in prison for continuing to detect pregnancy through ultrasound.

For Wentworth, the docket history supplied by the DOS began Sept. of 2017 while he and another named individual, who has not been arrested, were previously employed by Select Sires. Docket No. 1928-57-17, simply states “Respondents engaged in the practice of veterinary medicine without being properly licensed to do so under the Act” and describes this as “performed pregnancy examinations on cattle using ultrasound equipment.”

Both responded, and this led to a formal hearing, eventually in April of 2018, when the state’s expert witness, a University of Pennsylvania professor, could be available.

Both respondents appeared without representation. They testified on their own behalf and were cross-examined. In May 2018, the matter was closed and determinations were made that both men used ultrasound equipment to “determine pregnancy of customers’ cows” and to “determine if cows were in heat or had other medical issues.”

Noted in the history is this statement that begs more questions: “The economic savings to the cow’s owner, based on a positive pregnancy or negative heat result, are outweighed by the risk of harm to the cow posed by the unlicensed practice (of ultrasound).”

That brings us to April 2024, which the DOS will not comment on.

What we are left with on that is a downloaded copy of the PVMA complaint requesting contempt charges via the Commonwealth Court. Attached to the complaint were pictures from the arrested men’s facebook pages showing ultrasound pregnancy detection.

Bottomline, according to the DOS response: “The State Board of Veterinary Medicine is responsible for enforcing the Veterinary Medicine Act as enacted by the General Assembly. Questions about the provisions of the Act (including the exception in 63 Stat 485.32) should be directed to the legislature.”

This response makes the timing and manner of the arrests more curious, coming six months after the Pennsylvania House Ag Committee opened discussion to look at ways to address the statewide shortage of large animal veterinary practitioners, including the Veterinary Practice Act to see if modifications are needed for a “middle tier” to help Pennsylvania farmers cope.

For veterinary practices, the economics are increasingly difficult in attracting and keeping practitioners and vet technicians in the large animal domain. Their financial and time investments are significant, often graduating $250,000 in debt, and the trend is for more to go into small animal practice with pets to realize a return.

“No large animal practitioner is doing this — for the money,” said one central Pennsylvania vet.

Farmers identify with that. They have significant investments, see their costs rising, and in much of the state, see fewer large animal vets and prohibitive costs for basic services from consolidating companies on small farms vs. large ones, so they look for options, including doing more themselves.

“We have good vets, and I have done some ultrasounding with Rusty, but my vet comes in for herd health, and I keep a good relationship with my vet,” said a dairy farmer from Kirkwood in a Farmshine call April 24.

“Rusty is not trying to take work from vets. He is just trying to help the farmers and provide service for them. He has supported me 100% to help me make breeding decisions in my herd. He will even suggest a mating to a bull outside of his genetic lineup. Instead of just trying to get more business for himself, he highly encouraged and helped teach me how to inseminate my own cows. He’s a mentor and true hero. If anything, he’ll come out of this stronger,” the Kirkwood dairyman continued.

There must be middle ground here. Clarity, transparency and solutions are needed.

“As farmers, we put our bodies and souls into this. As everything consolidates in this industry, how do we compete? This is what extinction looks like,” said Ben Masemore, an eastern Pennsylvania dairy farmer and friend of Herr and Wentworth, who is involved in NoBull Sires, a separate business from NoBull Solutions.

He shared a partial statement written by Herr from his prison cell.

“To this day, we have never once had a farmer or caretaker complain to the state about any single issue. I know that we have a tremendous amount of support behind us, and I realize this will all get resolved. I will be a better husband, father, and person because of this entire experience, and for that I am grateful,” wrote Herr.

He expressed his hope that fair-minded people “can come together… to create a level playing field, one in which we can all work together for the greater good of the industry… I hope and pray that good can come out of this and that someday we can all look back on this time as a steppingstone for meaningful and lasting change.”

Thanking the NoBull team and supporters, and grieving what the families are enduring, Herr wrote: “Thank you all so very much for your coveted prayers and support. Thank you for your financial generosity. Keep the faith and be strong, God is always good. This will all be over soon.”

NoBull Defense Funds have been set up at two local banks to help with legal defense to get them home. Separately, an online fund has raised over $17,000 so far at https://www.givesendgo.com/nobull?utm_source=sharelink&utm_medium=copy_link&utm_campaign=nobull

-30-